TRIGGER WARNING: This essay examines historical slave narratives and includes discussion of slavery, sexual violence and exploitation, rape, human trafficking, physical and psychological abuse, forced reproduction, separation of families, infant and maternal death, religious abuse, and systemic racism. These topics are addressed in an academic and analytical context but may be distressing to some readers. Please proceed with care.

Introduction

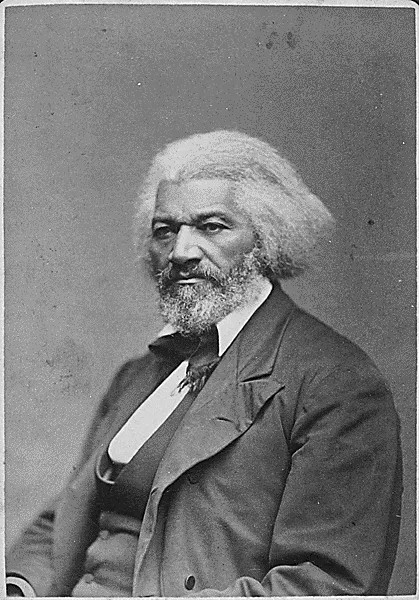

People brought to America for the purpose of enslavement were expected to learn English, adopt Christianity as their religion, and accept the social, cultural, and gender norms of white America. They had to leave behind their own languages, customs, and beliefs. Add to the confusion the conflicting messages created by abusive practices used to manipulate, control, and dominate the humans forced into slavery, and healthy psychological development becomes extremely difficult. Gender affected the daily experiences of enslaved people, the means by which they escaped to freedom, and the values by which their characters were judged once they told their stories. Frederick Douglass and Harriet Jacobs both endured the horrors of slavery and escaped to freedom, but their stories focus on different attributes to be exalted because they were appealing to white America and complying with their understanding of the gender norms expected of them.

Literature Review

Kimberly Drake writes of the concept of slaves being forced to accept the gender norms of American culture in her article “Rewriting the American Self…” Jennie Lightweis-Goff argues that Douglass could only have experienced some of his story as a male due to the social constraints about female violence and male independence at the time that would not have permitted the same actions for a woman. Both narratives describe sexual abuse of women to a greater degree than that of men. Jill LeRoy-Frazier asserts that Jacobs uses skills only a female would possess to escape slavery by way of tricking her captor with feigned innocence and a scheme to avoid seduction (LeRoy-Frazier). These sources support the ideas that male and female roles as perceived in American culture in the 1800’s contributed to differing experiences for black people both during enslavement and after they found freedom.

Theoretical Model

Because slaves were forced to accept the model of male and female as presented by the American culture in which they were enslaved, it would make sense to use a psychoanalytic lens to study gender differences as depicted in the narratives of people who have been enslaved. Several key concepts of the human psyche are severely interrupted by the institution of slavery including the following: the formation of a sense of self that is developed in relation to the mother, the ability to express and process trauma (instead of repression of trauma that leads to psychological imbalance), and healthy creation of individual and collective identities. The stories told by people traumatized by the violent institution of slavery are colored by their psychologically-affected views of themselves, the society in which they live, and the amount of healing they have been able to experience individually and collectively. Little healing was able to occur in a culture that continued to place burdens based on race and gender upon people who escaped from slavery.

Analysis – Male Independence v. Female Submission

The quest for freedom through struggle, physical feats, and courage are part of the age-old hero’s tale respected and admired by culture. However, in the 1800’s such heroism was admired and expected more as regards men than women. The cultural norm for women was submission and quiet acceptance, whereas men were expected to voice their complaint and strive for physical mastery in situations of inequity. Such double standards had root in Christian principles of hierarchy and their belief that gender roles were ordained by God. Only men were supposed to strive for independence. Women were expected to be in a household guided by a man of some sort, whether a father, husband, or older brother. Therefore, it seemed more natural in white American culture for a male slave to strike out on his own for freedom and build a new life – to become a self-made man. A woman desiring to do the same thing had hurdles to overcome besides those men had to endure. They also had to face the scrutiny of white cultural norms demanding that they find a place to submit to male dominance.

When Douglass narrates the moment that he decides to fight back against the white slave master Covey, readers are shocked and impressed by his courage. Prior to his revolt, Douglass masterfully details the tortures Covey enacts on the slaves in his employ after renting them from their owners. He has profited from a cheap labor system to work his land by building a “reputation as a slave breaker.” Douglass’s rebellion “subverts the oppressive powers” and demonstrates the beginnings of his psychological differentiation from the institution he has grown up in (Hoffman). He no longer accepts that slavery must be his reality and determines to separate himself from the system. The description is full of action and bloody, with Douglass the clear victor and a white slave master who “trembled like a leaf” (Douglass 368). He goes on to detail his seven-mile walk “covered in blood from head to toe” (Brown) to petition his owner for redress and looks “like a man who had escaped a den of wild beasts” (Douglass 367).

Another concept of male independence less available to females in the 1800’s was the ability to earn a living respectably. Douglass was able to do physical labor while in Boston and negotiate a percentage to keep for himself despite being a slave. It is not an easy affair and his enslaver ends up taking quite a bit of his money, but Douglass is able to save enough to use for his escape. Such industry is highly valued and admired for men and key to independence. Once free, he is able to support himself and his family with the wages he is able to earn. He buys a modest home and can furnish it comfortably with his income. Douglass also focuses on the lengths to which he strives to educate himself. Through sly actions and quick thinking, he sneaks books to read and bribes boys in the streets to give him lessons, while studying secretly to advance his knowledge. Such tenacity is viewed as commendable for a boy. Douglass harnesses the concepts esteemed by the dominant white American culture of education, physical power, and self-preservation and uses those to assist in developing his own individual identity, as well as to secure his own freedom (Webster).

In contrast, Jacobs mentions little of her path to literacy. Almost in passing and as a reason to let go of bitterness at not being freed, she mentions that her mistress taught her “to read and spell” (Jacobs 227). In another section when she is telling of the sexual advances that are becoming more frequent from her master Mr. Flint, she writes, “One day he caught me teaching myself to write” (Jacobs online 49). If anything, she downplays her ability to read and write and uses her skills to conceal rather than proclaim (Le-Roy Frazier 154). For example, Mr. Flint begins sending her notes filled with seductive language. She claims she cannot read them. Later, when hiding in the attic, she sends letters covertly from cities in the North to trick Mr. Flint and keep him from knowing her true location. She also feigns innocence multiple times about the meaning of Mr. Flint’s intentions. Her refusal to participate in his advances buys her time and admiration from white audiences reading her accounts because a woman is expected to be virtuous in sexual matters. Even her eventual affair with another white man resulting in several children is presented as an understandable moral failing after years of suggestive training at the hands of Mr. Flint and her foiled marriage to an eligible freed black man.

Rather than focus on the independence and strength necessary for escape, Jacobs highlights the communal assistance she receives. She describes the family efforts to protect her hiding place in the attic while feeding and nurturing her the best they can. The focus continues to shine on the grandmother’s sacrifices and the generations of love built into her concealment. When she finally escapes to the North, she remains determined to liberate her children and reunite her family. This family-oriented focus was the socially acceptable mindset for a woman in American culture in the 1800’s. Not only would Jacobs receive more support from white Christian readers for this attitude, but it would correspond to the psychological development of a woman living in that culture. She is also unable to write about earning money to aid in escape because she does not have a way to do that. Even once she is free, it is difficult for her to earn a living except in housekeeping or childcare. There are few opportunities for women in the labor force in the 1800’s. Jacobs says she dreams of owning her own small home where her daughter can be with her, but recognizes that her vision will probably never become a reality. Without marriage which would provide the income of a man, it is nearly impossible for a woman to live independently and afford a home of her own. She is bound by the restrictions of her time and place. The desire to be independent is seen “as a deviation” in a woman, whereas it is normal for a man (Drake 98).

Analysis – Sexual Exploitation

The brunt of sexual exploitation fell to women to endure in slavery. Jacobs claims that slavery “is far more terrible for women” because of the sexual abuse they must endure (Jacobs 240). Their white masters deemed them property with which they had the right to copulate (increasing their wealth by producing more property.) Douglass gives the example of an enslaved woman named Caroline who was purchased for the express purpose of being a “breeder” (Douglass 364). They also viewed slaves as possessions they could use to fulfil their own sexual pleasures. The enslaved women did not have a say in the matter and were often raped if they refused the master’s advances. Certainly, enslaved men also experienced sexual exploitation, but the social mores were less forgiving for women masters participating in such behavior than for that of male masters, so the instances were less frequent. Jacobs mentions one instance of an enslaved male being sexually exploited in her narrative by the daughter of a slave owner. The girl forces an enslaved man who is “the most brutalized, over whom her authority could be exercised with less fear of exposure” to impregnated her. Then she gives him documents asserting his freedom and sends him to another state (Jacobs online 81).

Enslaved people were often unable to form healthy sexual identities due to the constant fear of abuse, pregnancy resulting in children doomed to lives of slavery, and the threat of offspring being sold off and sent away. They were also often not permitted to legally marry and told by their newly adopted Christian religion (which they were supposed to obey) that marriage was a requirement for sex. Any sex that occurred for slaves was viewed as sinful, so many struggled with feelings of guilt for giving in to natural human desires. These conflicting emotional struggles added to the trauma and turmoil many slaves experienced on a daily basis.

After being sexually assaulted and traumatized, enslaved people were often blamed for the ensuing pregnancies or jealousies of the spouse. Jacobs was mistreated, scrutinized, yelled at, hit, and manipulated frequently by either Mr. or Mrs. Flint related to the marital friction caused by Mr. Flint’s preoccupation with Jacobs. Jacobs was even afraid to speak to her grandmother about the constant incursions on her propriety because she was ashamed and afraid she would be blamed for the situation. Women were often considered at least in part at fault for the sexual indiscretions of the men. For example, Jacobs tells of a white woman furious that her husband had sex with a slave girl. She stands by the beside of the girl who is dying after giving birth and mocks her, saying she is glad and that the girl deserves to die (Jacobs 230). She “rejoices in her suffering” (Zimmerman). The white woman goes on to declare that both the girl and the child will not go to heaven, implying that the girl’s behavior is too sinful and the bastard child such an abomination that not even God will accept them. Her declaration is the ultimate hypocritical irony since the very religion, impregnation, and death have been brought on by the slavery inflicted upon them by the white woman and her husband in the first place. Enslaved people are forced to accept the American norms thrust upon them in order to create identities, then forbidden from actually participating fully in those norms by their enslavers. The result is a confusion of identity that is fractured (Drake 92).

Analysis – Maintaining Familial Structure for Generations

Most forms of mistreatment visited upon enslaved people appears to affect both genders equally, however, a greater degree of emotional trauma seems to be sustained by women attempting to maintain familial structures to manage care of multiple generations. Enslaved women are expected to be wet-nurses and caregivers to white babies and behave in a nurturing maternal fashion. They are expected to bear children as deemed fit by the masters in order to add to his wealth. They are required to be mothers, but only as long as the master deems it expedient. They are expected to turn off their mothering instincts and accept the ripping of their children from their arms if that is the decision of the owner. They were considered “chattel, entirely subject to the will of another” (Jacobs 234). Sometimes babies were sold shortly after birth to protect the dignity of the slave owner who might not want people to know he had sex with his slave (Burke). Douglass says that “It was a common custom, in the part of Maryland from which I ran away, to part children from their mothers at a very early age. Frequently, before the child has reached his twelfth month, its mother is taken from it and hired out on some farm a considerable distance off, and the child is placed under the care of an old woman, too old for field labor.” Douglass suggests that the point of this practice was to “hinder the development of the child’s affection toward its mother, and to blunt and destroy the natural affection of the mother for the child” (Douglass 338). The result of this also damages the psychological development of a child who needs to be able to form bonds in order to reach important milestones of growth. Douglass did not know much of his own mother. She was a field hand and had to walk seven miles after work to come see him, so she was only able to make the trip three or four times before her early death.

Mothers who are able to raise their children and bond with them still run the risk of seeing their children sold off when they reach an age at which they can do more labor. When Jacobs’s grandmother’s master died, her grandmother’s children were divvied up as inheritance to each of his four children. Because she had five children, her youngest son was sold (to keep things even and fair) and the money from his sale split between the four heirs. He was only 10 years old (Jacobs 225). Jacobs’s grandmother had multiple generations of children to attempt to care for. It was the grandmother who raised them when Jacobs decided to go into hiding and eventually escape. Though she could watch their growth from her attic peephole, Jacobs was unable to assist in their care in any way. It is significant that Jacobs hides for seven years in the attic watching over her children. Her escape from slavery still keeps her bound to her children who are in slavery, unlike Douglass who simply disappears without a trace and relinquishes all ties. It is not always as easy for women to leave their families behind and escape because so many people depend on them for literal survival. Mothers who were permitted to keep their children often had to find ways to feed them and care for them if their masters did not provide enough food or clothing. They also had to put the needs of their white charges ahead of their own children. Jacobs narrates that her own mother had to be weaned at only three months old because her grandmother was a wet nurse for the white baby of her master. They wanted to be sure that their baby was getting enough food. They did not care if the wet nurse’s own child received enough nourishment.

Women of childbearing age also had to endure the frequent physical stress of pregnancy, difficult labor without proper resources, and increased infant and maternal mortality rates due to poor prenatal care and unsafe living conditions. As mentioned previously, Jacobs tells of the woman and child who died in childbirth and were mocked by the white wife of the slave owner. The dying woman’s mother was by her side through the whole ordeal, hoping to save her own child and grandchild. She is the one who exclaims, “I hope my poor child will soon be in heaven,” and is blasted by the woman for even hoping her daughter could enter heaven (Jacobs 230). Jacobs herself was mistreated by her slave owner only four days after giving birth to her child. She was weak and having a slow recovery, but he made her stand so that he could verbally abuse her as he examined the baby. The ordeal caused her to lose consciousness and fall to the ground with the baby in her arms. She thought she might die and says, “I should have been glad to be released by death, though I had lived only nineteen years” (Jacobs 241). Enslaved women were tortured with the knowledge that their daughters would have to endure the same sexual exploitation as them. There was nothing they could do to protect their young daughters from being raped (Hoffman). Jacobs’s most earnest prayer was probably that of every black parent who was enslaved. “I prayed that she might never feel the weight of slavery’s chain” (Jacobs 241).

Women who were caregivers for multiple generations of white and black children often found themselves without care once they were ailing or unable to be of use to the white slave owners. Douglass says the metaphorical straw that broke the camel’s back for him as regards the evils of slavery was the “ingratitude to my poor old grandmother” (Douglass 357). It broke his heart to find out that his grandmother whose service spanned lifetimes of white owners from birth to death was rewarded with being turned out into a lonely forest to die. They put her there in a little mud hut and left her to fend for herself in complete isolation, basically waiting to die. How can such cruelty and inhumanity possibly permit the victims to develop any semblance of healthy psyches?

Results and Conclusion

It is no wonder that inter-generational trauma and complicated painful legacies continue to be unearthed in the collective consciousness of the black descendants of enslaved people in America. Enslaved men and women were forced to create identities influenced by American cultural norms, but were denied the tools, resources, and freedom to do so. They were actively thwarted at every turn by opposing demands such as men being required to act in a subservient manner, though male culture admires dominance and independence. Women were required to work hard like men and “breed like an animal”, though female culture expects domesticity and protection of their virginity (Drake 94). It is no wonder that people of color have grievances toward white America and the lack of empathy for their current situation in the socio-economic, political, and cultural milieu in which they are forced to exist.

Works Cited

Brown, Danisha. “2-2 Blog – Female and Male Slave Narratives.” LIT-550-Q3765 Black

Literary Traditions 21T23. SNHU, Mar. 3, 2021, learn.snhu.edu/d2l/le/content/ 673815/viewContent/12036773/View

Burk, Christine. “2-2 Blog – Female and Male Slave Narratives.” LIT-550-Q3765 Black Literary Traditions 21T23. SNHU, Mar. 3, 2021, learn.snhu.edu/d2l/le/content/ 673815/viewContent/12036773/View

Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. The Norton Anthology of African American Literature Third Edition Volume 1. W.W. Norton & Company, 2014.

Drake, Kimberly. “Rewriting the American Self: Race, Gender, and Identity in the Autobiographies of Frederick Douglass and Harriet Jacobs.” MELUS, vol. 22, no. 4, 1997, pp. 91–108. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/467991. Accessed 28 Mar. 2021.

Hoffman, Catherine. “2-2 Blog – Female and Male Slave Narratives.” LIT-550-Q3765 Black

Literary Traditions 21T23. SNHU, Mar. 3, 2021, learn.snhu.edu/d2l/le/content/673815/ viewContent/12036773/View

Jacobs, Harriet. Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. The Norton Anthology of African American Literature Third Edition Volume 1. W.W. Norton & Company, 2014.

LeRoy-Frazier, Jill. “’Reader, my story end with freedom:’ Literacy, Authorship, and Gender in Harriet Jacobs’s ‘Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.’” Obsidian III. 5(1):152-161; North Carolina Arts Council and the national Endowment for the Arts in Washington, D.C., 2004, eds-b-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.snhu.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=6&sid=f7b7c976-06b0-4ccb-b9b8-d8a17ab92ce7%40sessionmgr101

Lightweis-Goff, Jennie. “Interior Travelogues and ‘Inside Views’: Gender, Urbanity, and the Genre of the Slave Narrative.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture & Society, 00979740, Autumn2015, Vol. 41, Issue 1. eds-b-ebscohost-com.ezproxy.snhu.edu/eds/detail/detail? vid=3&sid=f7b7c976-06b0-4ccb-b9b8-d8a17ab92ce7%40sessionmgr101&bdata=JnNpd GU9ZWRzLWxpdmUmc2NvcGU9c2l0ZQ%3d%3d#AN=108825638&db=sih

Webster, Emily. “2-2 Blog – Female and Male Slave Narratives.” LIT-550-Q3765 Black Literary Traditions 21T23. SNHU, Mar. 3, 2021, learn.snhu.edu/d2l/le/content/673815/ viewContent/12036773/View

Zimmerman, Bernadine. “2-2 Blog – Female and Male Slave Narratives.” LIT-550-Q3765 Black Literary Traditions 21T23. SNHU, Mar. 3, 2021, learn.snhu.edu/d2l/le/content/673815/ viewContent/12036773/View