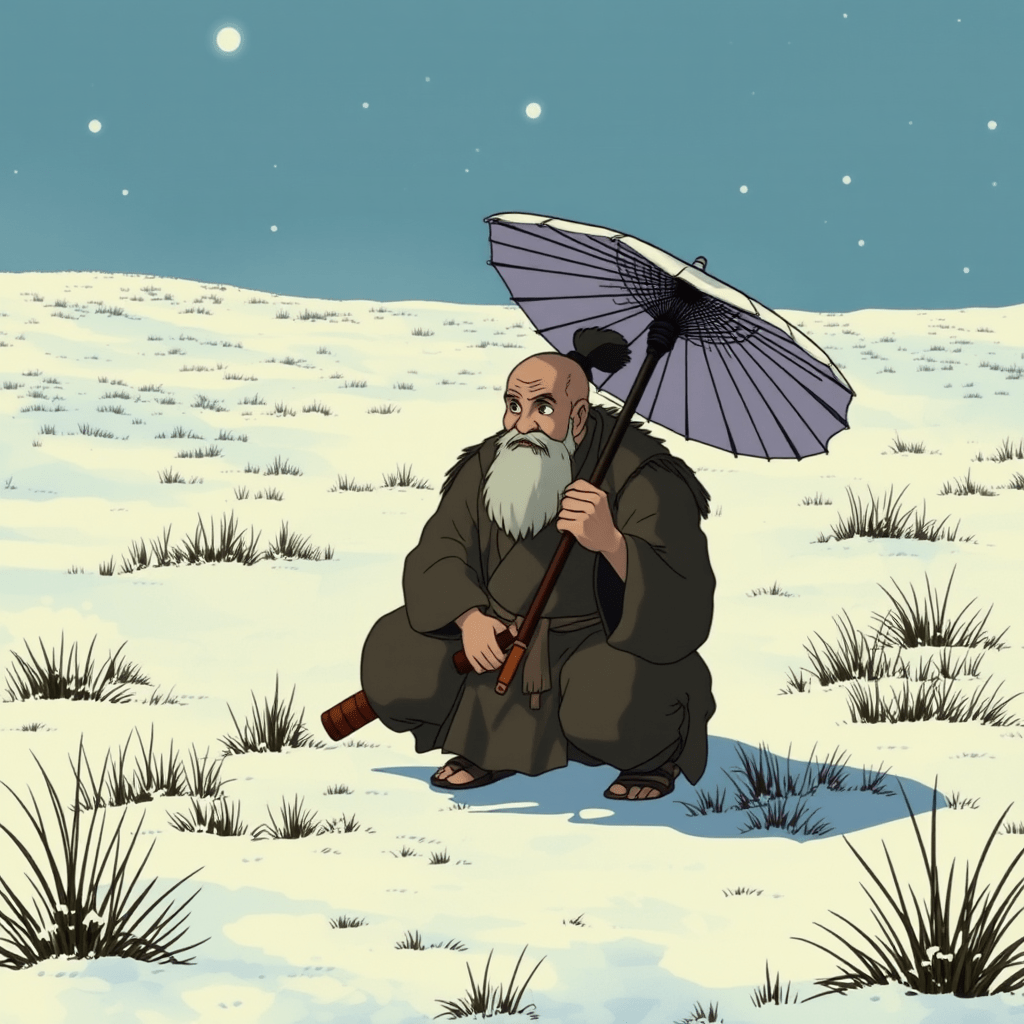

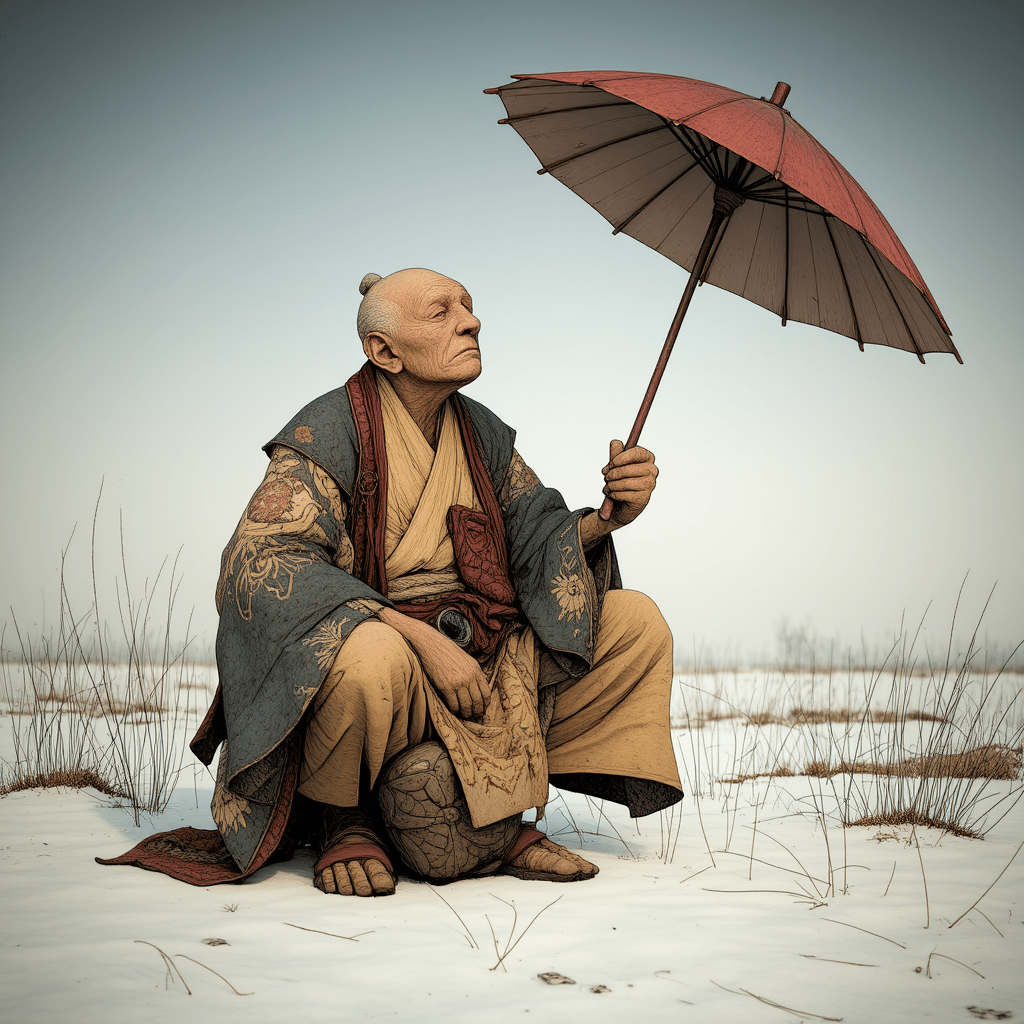

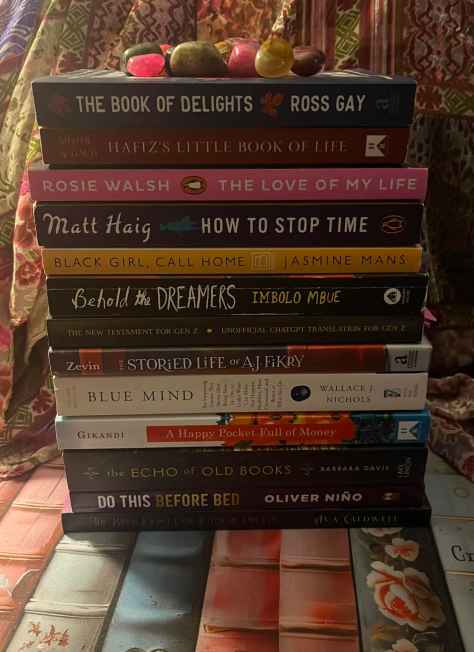

I am reading Hafiz’s Little Book of Life, poetry by Hafiz-e Shirazi. He is challenging me to become more comfortable with ambiguity. I will share his poem and some of my thoughts on his poem (sometimes with the help of experts when the concepts are too hard for me), followed by a poem and some art inspired by his poem.

Hafiz’s Poem 32:

While you slept

The caravan has moved on

The desert is up ahead

Some thoughts:

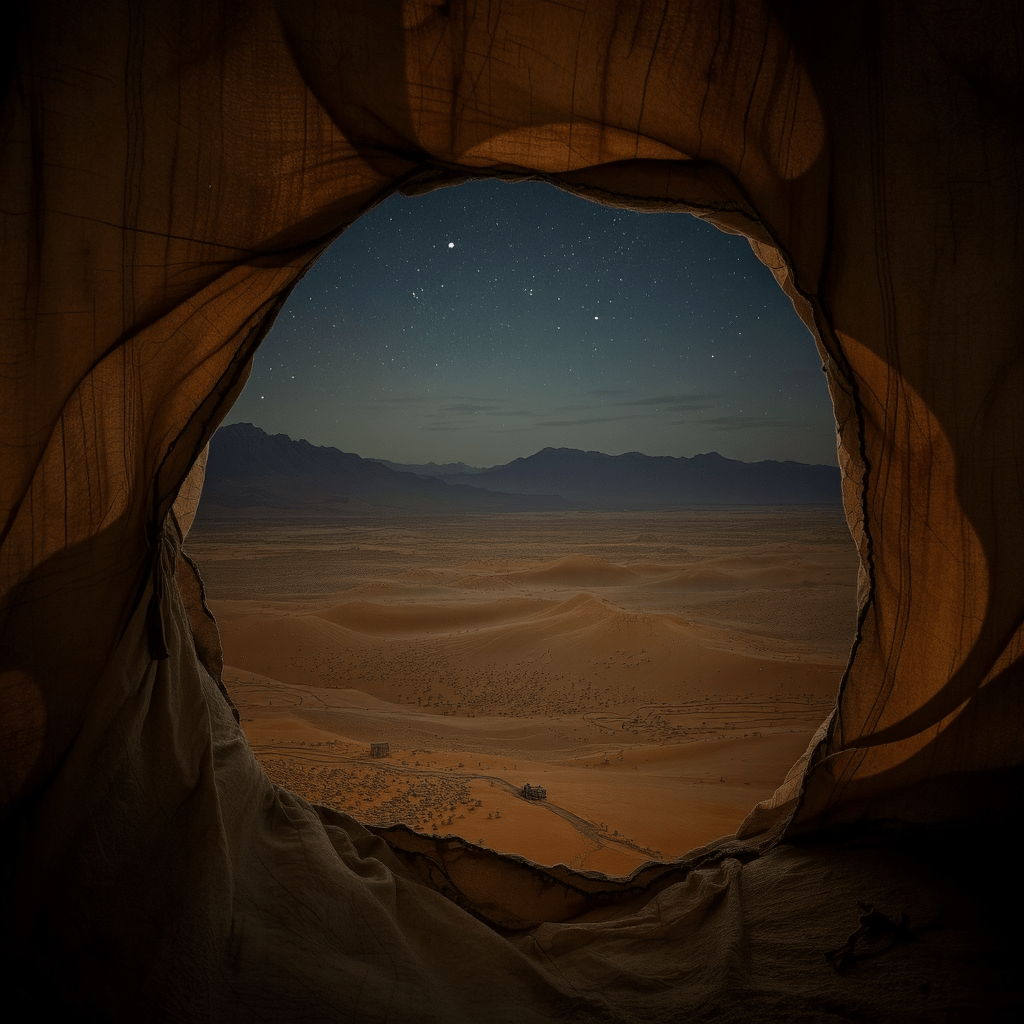

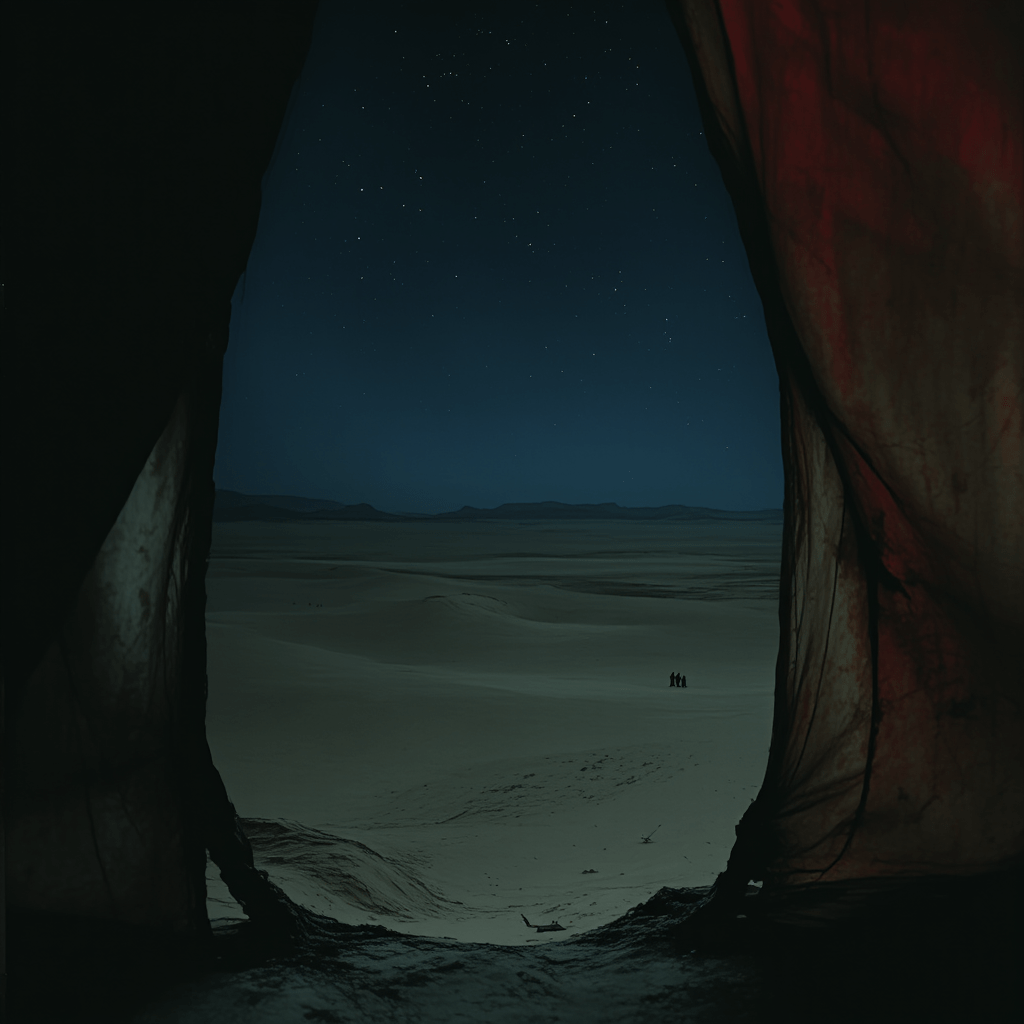

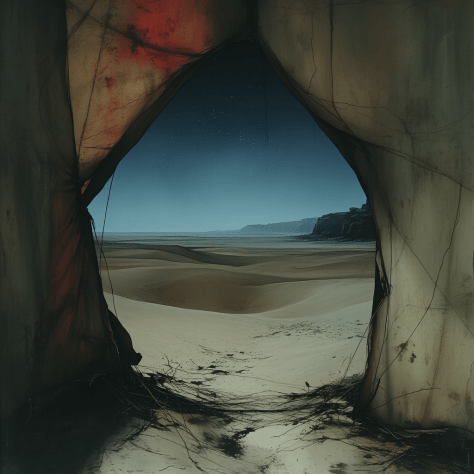

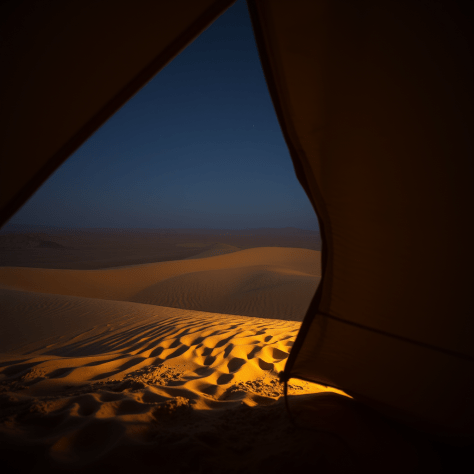

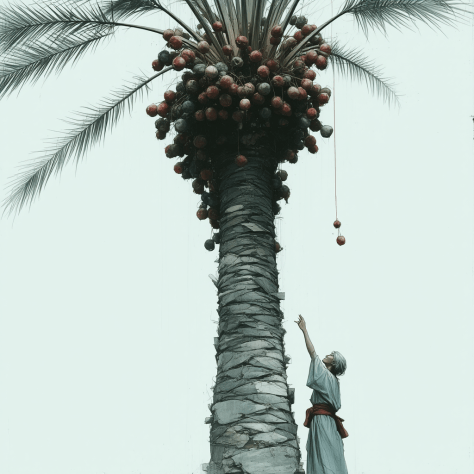

As an intense sleeper in need of a ridiculous amount of sleep, this poem annoys me at the literal level. But if I look at it a bit more metaphorically, I can see what the poet is saying. We all must sleep, rest, withdraw from the world at times for healing and downtime. But isolation can become a habit if we let it. It is peaceful in our own tent, with our soft furnishings, and our quiet comfort zones. Outside is the noisy bunch with their opinions and foibles and, sometimes, annoying ways. But there are important qualities to community that we must remember to consider. It is only through community that we grow as people who can empathize with others, connect for companionship, and be nurtured and remembered. And in Hafiz’s time, there was safety, especially when travelling through the desert. It could be very dangerous to find yourself alone in a wilderness landscape. You might not survive. I suppose it is a good warning/reminder to find balance in our isolative ways if we are prone to such patterns.

My Poem 32:

While we slept,

energy continued to transition

from typewriters into clouds,

from broadcast to streams,

from nickels and dimes into crypto,

from desktop computers to quantum AI.

While we slept,

families continued to transition

from mother, father, two children to

whoever can cobble a life together,

whatever the gender expression

or lack thereof, or anywhere in between,

from white with white only to

beautiful hues of blended shades.

While we slept,

societies continued to transition

from patriarchal oppressive regimes

to the beginnings of equality and inclusion,

from workplace discrimination to

women in leadership roles, wheelchair ramps,

climate change and mental health awareness.

While we slept,

religious institutions continued to transition

from exclusive to more inclusive,

from in person only to online participatory options,

from fundamentalist to deconstructionist,

from male-only leadership to some women in high places.

While we slept,

culture continued to transition

from consumerism to minimalism,

from the status quo to conversations about privilege,

from fat-shaming to body positivity,

from nature destruction to environmental consciousness,

from acceptance to accountability.

When we wake,

will we bury our heads in the sand

and demand a halt to change, a return to the past,

or will we lift our chins, with eyes wide open, minds alert,

mouths slightly agape, and join the caravan?

The desert is up ahead.

It is vast and wide, and we will be left behind

in our ruts of “we know best” and “tradition is all,”

while the great adventure of life moves on without us.

Hafiz. Hafiz’s Little Book of Life. Translated by Erfan Mojib and Gary Gach, Hampton Roads Publishing, 2023.