TRIGGER WARNING: This essay contains discussion of racism, police violence, death, and racial trauma in a critical and literary context.

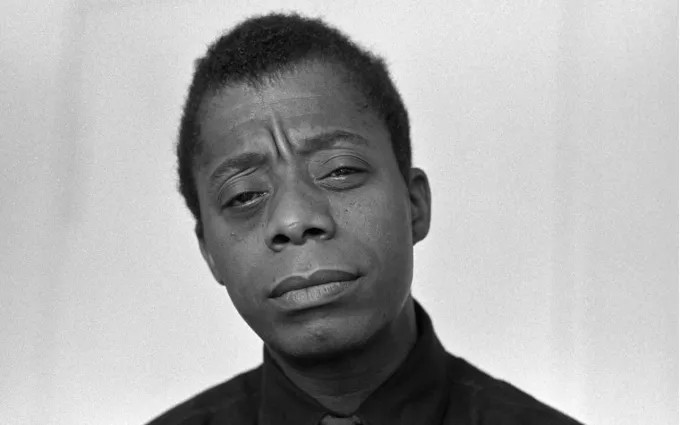

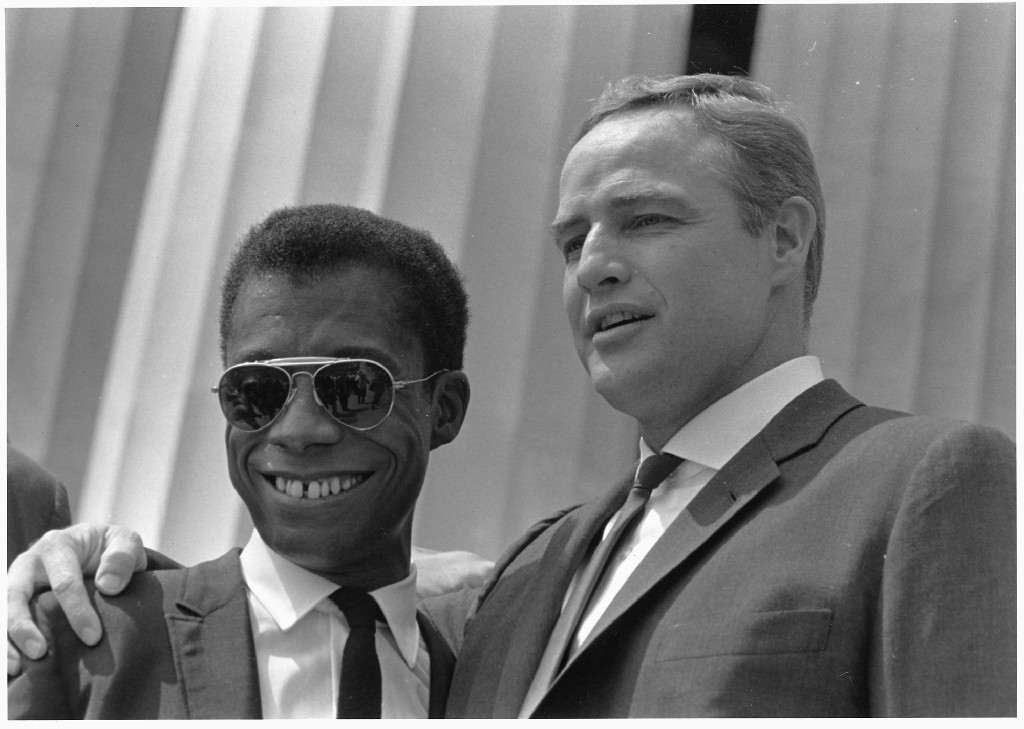

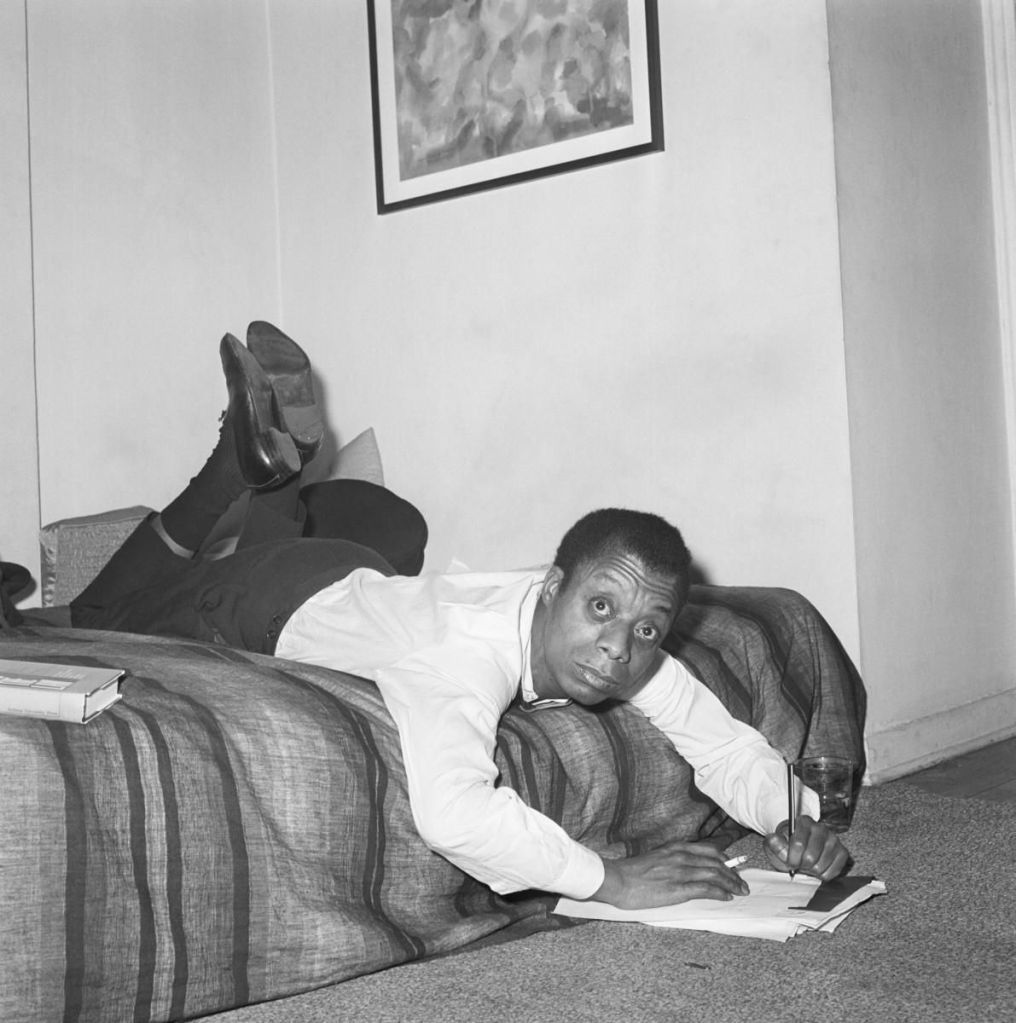

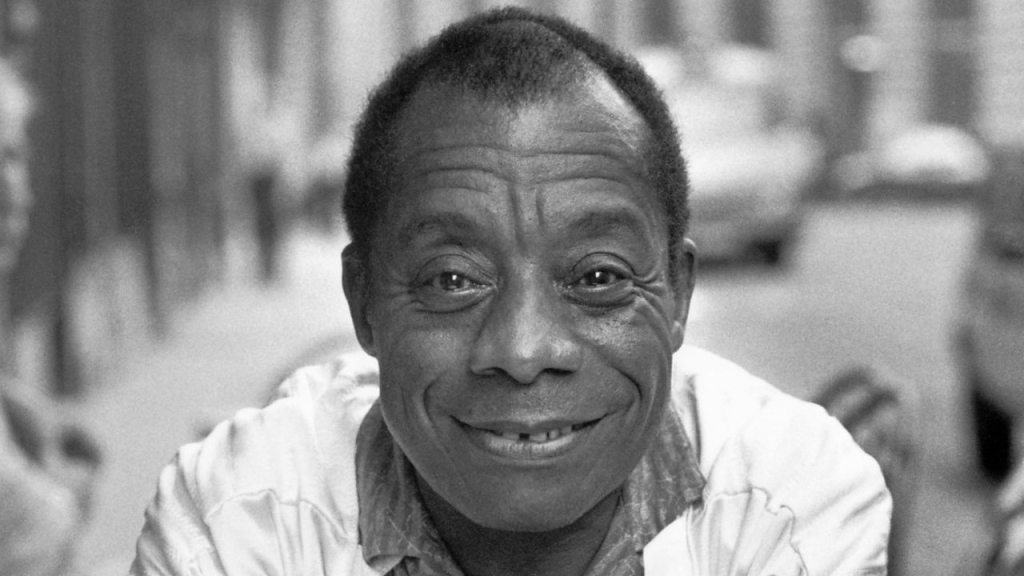

James Baldwin’s letter to his nephew is both personal and national in appeal as a publicly published letter to inspire black Americans and scold white. Likewise, Ta-Nehisi Coates’s letter to his son reveals extremely personal details that may encourage black Americans and spur white Americans to pick up the mantle of struggle alongside their darker brothers. Both letters speak to the lack of equality present for black Americans and the need for white mindset change for improvement to occur.

In “A Letter to my Nephew”, Baldwin moves chronologically through his life telling the tale of his nephew’s origins. He weaves into the personal story of his family’s tale, the historical context that affects them all including the results of geographic constraints, political, economic, legal, etc. that make life harder for African Americans. For example, Baldwin writes, “This innocent country set you down in a ghetto in which, in fact, it intended that you should perish.” He goes on to attempt to explain the thinking of the white “countrymen” that would permit such unfair treatment of their brothers. “They are in effect still trapped in a history which they do not understand and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it.” This calling out of uninformed white people is the way Baldwin throws down his gauntlet. It is up to everyone to become informed and prepare for change. The rest of the letter is encouragement to his nephew to be brave and loving as he continues the fight. And near the end he makes the inclusive statement, “We cannot be free until they are free” (Baldwin). He flips the idea of oppression on its head. The oppressor is the one who is in chains due to their refusal to educate themselves and grow with the changes that terrify them.

Coates’s Between the World and Me tells the tale of significant points in his life, including the birth of his son, but it is not strictly chronological. He jumps around in time, beginning with a recent interview and meanders through different time periods throughout the book. Coates weaves historical incidents like police shootings of unarmed black people, redefines terms to his preferences – terms like race and racism, dreamers, and white – glorifies black culture including music, art, literature, and fashion, and includes interviews with mothers who lost children to police violence. His letter feels at once even more personal in connection to his son and, at the same time, even more broadly an accusation of all Americans complicit in the conspiracy to oppress black people.

As Coates meanders through white on black oppression, he addresses his own fear that grew out of living while black. He admits that he does not want to raise his son with the same fearful perspective but also recognizes that fear might be what has helped him stay alive. He tells stories showing that constant awareness of potential danger is necessary for safety. He also admits that hyper-sensitivity to danger sometimes removes the ability to live in the moment and enjoy the present. Using so many resources to remain in fight or flight mode steals reserves that could have been used for learning, experiencing, connecting, and joy. These are the things that make him angry, that make him feel hopeless and make him realize that there is still much struggle left for all to endure. He encourages his son to struggle but does not seem to call him to love the same as Baldwin. He encourages him to endure but does not provide the same hopeful outlook as Baldwin. It seems like a public shaming of white America. They have continued to oppress, even in the face of countless opportunities to change. Perhaps Coates is hoping to guilt them into an awakening. Coates’s letter ends with witnessing the same crumbling infrastructure that has been the setting for so many black lives – “and I felt the fear” (Coates 152).

Works Cited

Baldwin, James. “A Letter to My Nephew.” The Progressive. 1 Dec, 1962, progressive.org/magazine/letter-nephew/

Coates, Ta-Nehisi. Between the World and Me. Spiegel & Grau, 2015.