TRIGGER WARNING: This essay discusses patriarchal oppression, gender-based violence and punishment, sexual shaming, social ostracism, and cultural trauma. These topics are examined in a literary and analytical context.

The Woman Warrior by Maxine Hong Kingston paints a picture of harsh expectations placed upon Chinese/Chinese American women. Though the narrator rejects some of the notions and attempts to forge her own path, she still feels duty-bound to uphold some of the traditions. Each section of the book focuses on a different woman and explores the expectations placed upon her specific to the time and place where that portion of the story is set.

For instance, No Name Woman lives in a village in China early in the 20th Century. She is expected to remain “pure” (no sex) until her husband’s return from war. Her sexual desires are not a consideration and her ensuing pregnancy is punished by shaming the family and destroying their crops, livestock, and stored foods. The family then disowns her and never speaks her name again, ensuring she would “suffer forever, even after death” (16). There is no mention of the man who must have impregnated her on the part of the villagers or her family. She must bear the full weight of the “crime” of having sex and becoming pregnant.

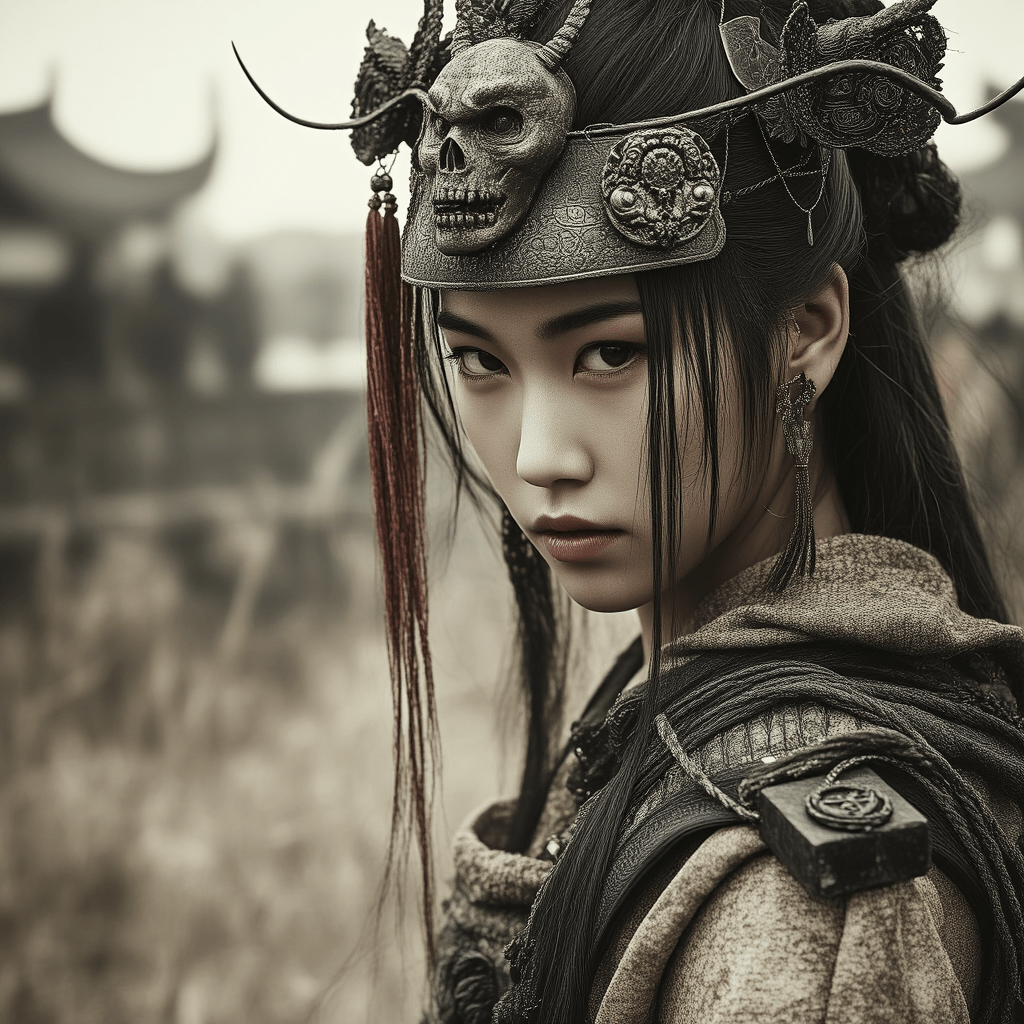

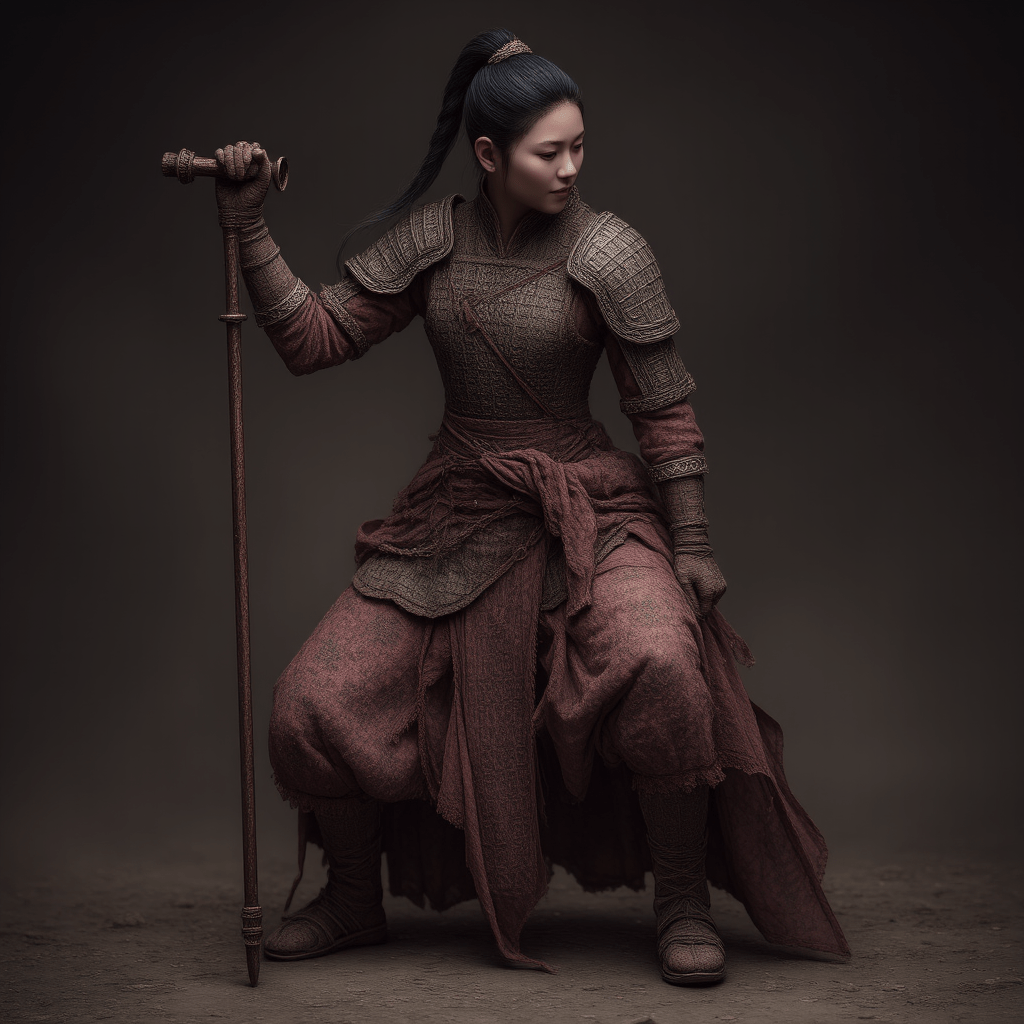

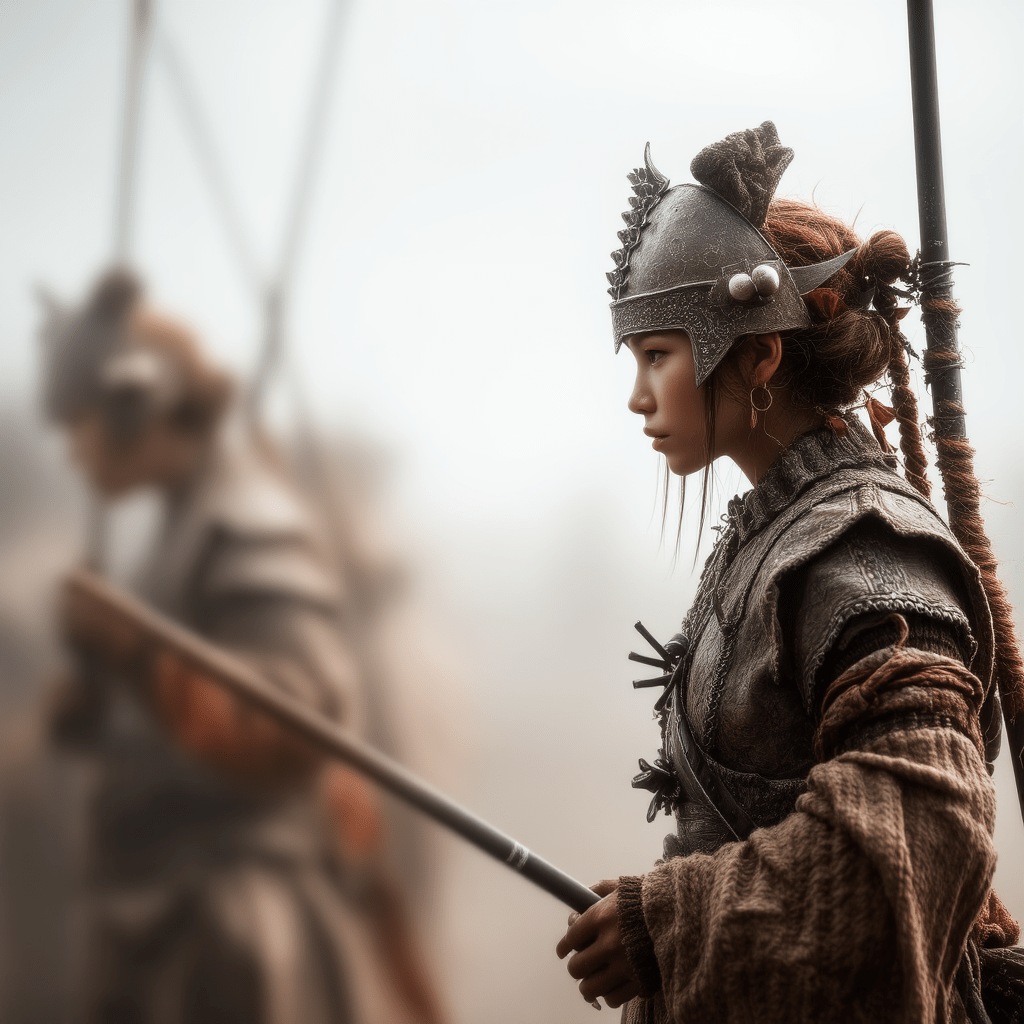

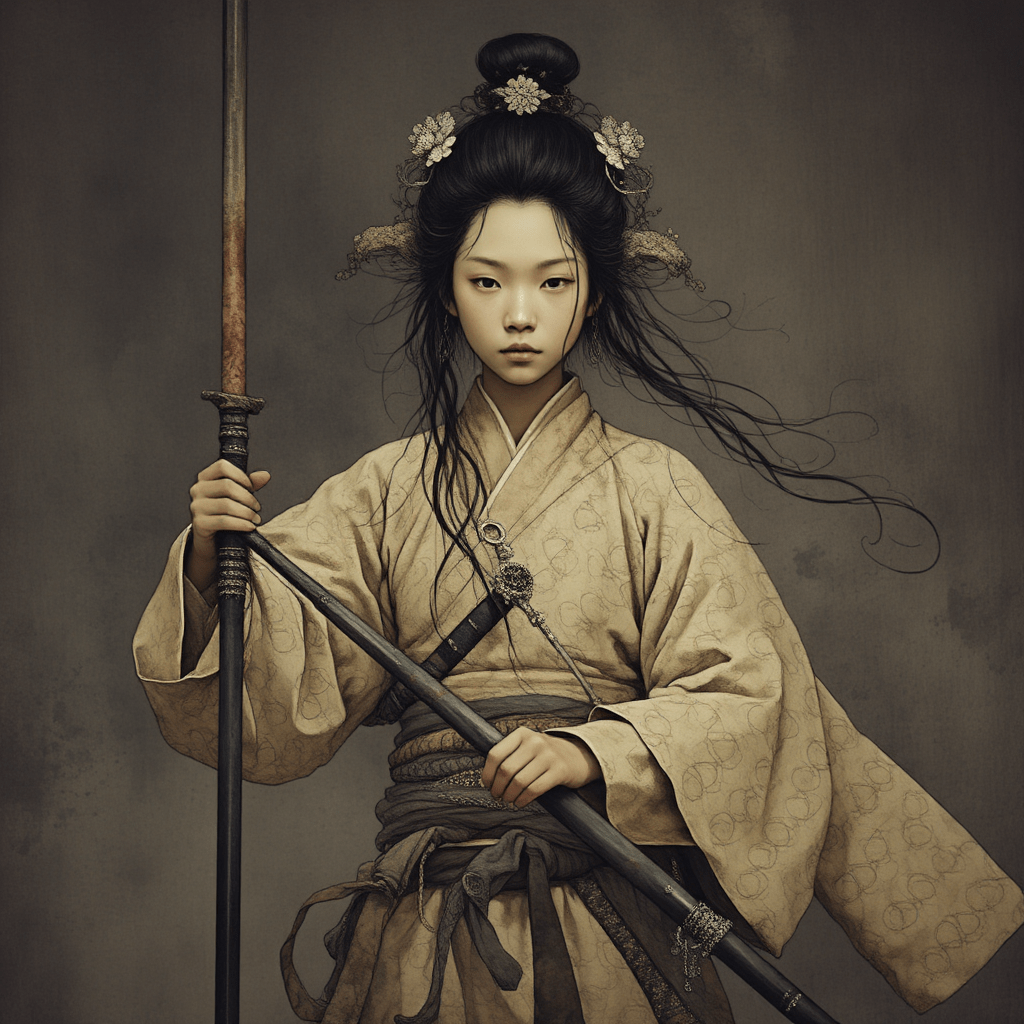

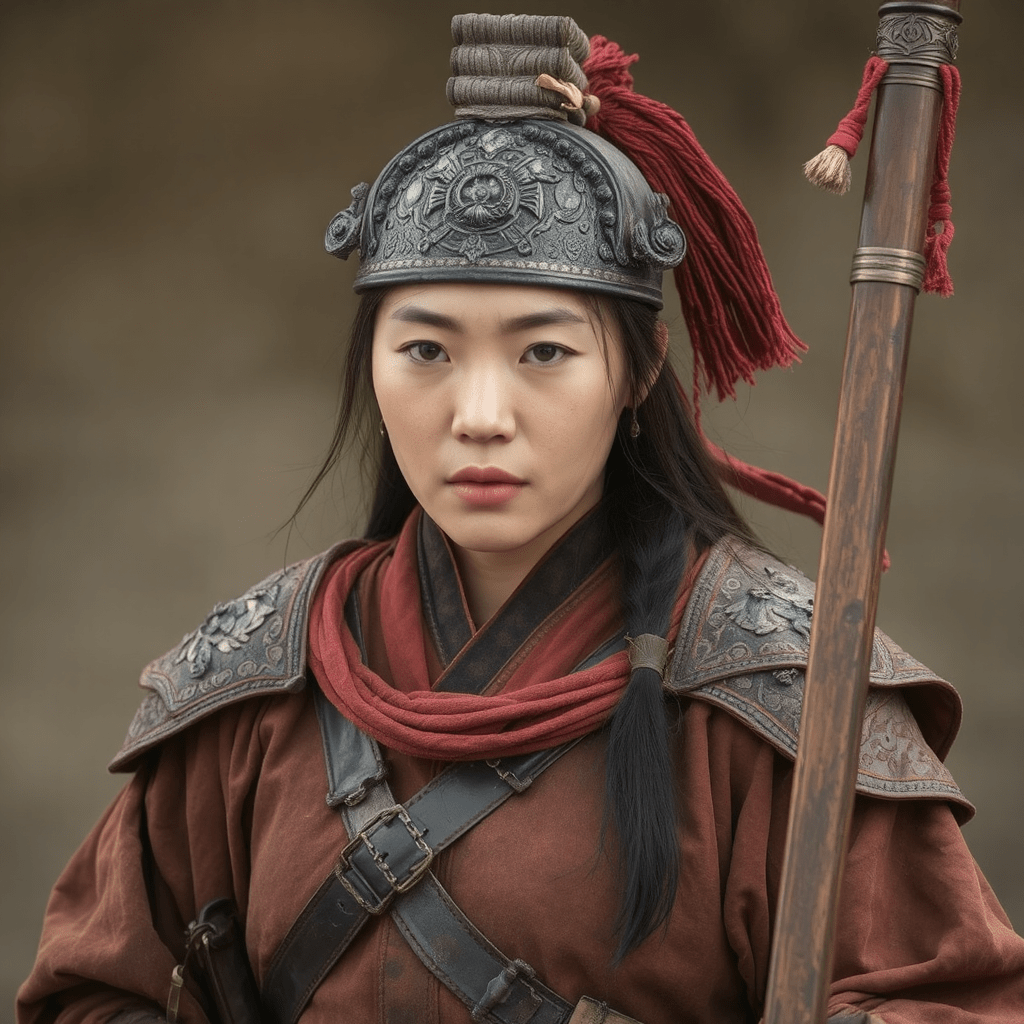

Fa-Mulan in the “White Tigers” section of the book becomes the greatest hero in the land saving her family, her village, and her country from evil rulers. She is a warrior, savior, and leader who has trained for 14 years to become the best hero possible. Yet, once her mission ends, she is expected to return to the “appropriate” role of wife, daughter-in-law, mother. There is no option for leadership in her world. This character is thought to have lived sometime around the year 500 in China. Women were not supposed to use their brains or their brawn, except in service to men. Any woman who attempted to pass as male enter the military or school would be executed, “no matter how bravely they fought or how high they scored on the examinations” (19).

The “Shaman” section about Brave Orchid shows the variety of domestic expectations placed on Chinese women. Brave Orchid lives the first half of her life in China and the second half in America spanning the 20th Century. She works as a medical practitioner in China and then in the family laundry business in America. Besides working long hours, she picks tomatoes as a part-time job to make more money, does all the cooking and cleaning, and manages all aspects of the household. She is also expected to carry on the traditions of the culture by keeping the rituals, ceremonies, and talk story alive so that it will pass on to the next generation. She must also protect everyone’s souls by calling them back when they have forgotten their way home. Brave Orchid’s eyes fill with tears as she tells her adult daughter, “I work so hard” (103). Chinese women are unrealistically expected to do more than their fair share of the work.

The section “At the Western Palace” highlights the way Chinese women in the past had little power in marital situations. Their partners were chosen for them and husbands might take multiple wives. The women were expected to tolerate and support these traditions without question. When Moon Orchid comes to America in the 1950’s, she is confronted by a different reality in which women have more rights and her husband rejects their marriage. She is expected to accept his continued financial support without living as his wife. Chinese American women seem to still have parents attempting to meddle with selecting their potential suitors according to the narrator.

In the final section “A Song For a Barbarian Reed Pipe” the narrator implies that a “good” Chinese American girl in America in the 1950’s should be able to speak fluent English and Chinese. She should attend Chinese school and American school. It is an interesting note that “good manners…is the same word as traditions” in Chinese (171). To please the Chinese, she should be obedient and demure, soft-spoken, and graceful, domestically competent – able to cook, clean, serve, and heal, and pleasant in interactions while not making eye contact, use opposites to confuse evil spirits, keep all Chinese traditions, send money to family members in China, lie to Americans so no one can trap her or deport her or trick her somehow, and remember that men are valued more highly than women. To please the Americans, she should be assertive and firm of voice, intelligent, sexy, able to defend herself, and independent making strong eye contact, speaking from a place of science and logic rather than any mention of evil spirits, creating a comfortable lifestyle that is America-focused, be a patriot, and believe that women and men are equal. A Chinese American woman is expected to do all of this and figure out how to be healthy, happy, and prosperous without driving herself crazy over the paradoxes such disparate expectations create.

Works Cited

Kingston, Maxine. The Woman Warrior – Memoirs of a Girlhood Among Ghosts. Vintage Books, New York, 1975.