TRIGGER WARNING: This essay discusses gender roles, sexuality, cultural expectations, and references to violence and death in a literary context.

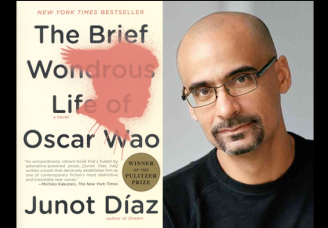

Oscar de Leon, the main protagonist of Junot Diaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, is woefully terrible with the ladies. “His lack of game” is noticed by everyone around him and he often cries “in the bathroom where nobody could hear him” over “his love of some girl or another” (Diaz 23-24). A pickup line he actually uses is, “If you were in my game I would give you an eighteen Charisma” (Diaz 174). Though many people offer advice including Yunior, his uncle, and Lola, none of it sticks. Yunior says “he tried to get him to stop hollering at strange girls on the street…” but Oscar insisted that “nothing else has any efficacy, I might as well be myself” (Diaz 174).

When Oscar finally falls for a woman who seems to accept him, Ybon, she is the wrong woman according to Dominican culture. She is too old, too promiscuous, too “claimed-by-a-cop” already. However, he perseveres and gets himself killed in the process. Whether that is stubbornness, machismo, or crazy (maybe all three) it is certainly along the lines of grabbing “a muchacha, y meteselo” like his uncle advised (Diaz 24). And when he finally gets Ybon to himself for a week, it sounds as though he makes the most of his time enjoying sexual exploits like the best of them. However, even then, what he really loves are the little unanticipated intimacies like “combing her hair”, the way she would “sit on his lap”, or “watching her walk naked to the bathroom” (Diaz 334). He is well-rounded in his appreciation of the entire experience, which is more admirable than simply enjoying the sex. At the end when he says, “The beauty! The beauty!” it sounds like a counter to Conrad’s Heart of Darkness “The horror! The horror!” (Diaz 334, Conrad 12). To him, the sacrifice is worth it.

If the willingness to face violence or defend women against violence is any part of machismo, then Oscar qualifies as a Dominican male at least a few times in his life. He takes a gun and is willing to confront Manny in order to defend Ana (Diaz 47). Thankfully, Manny does not show up and Oscar gets to remain a lover, not a fighter. He knows he could be beaten, but continues spending time with Ybon right up until he is beaten near to death (Diaz 298-299). And he knows he will be killed for his determination to be with Ybon in the end. He faces his death with the fervor of “a hero, an avenger”, and tells his killers he will be waiting for them on the other side (Diaz 320). That takes some guts.

To the degree that the American ideal is “all men are created equal”, Oscar’s lack of “Dominicanness” makes him more American. But, suffice it to say, America does not do a great job with equality either. Both cultures still have a long way to go toward treating all people with the decency and kindness that humans deserve despite gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, etc. Perhaps that is why Yunior talks about Oscar’s niece Isis as the future hope of breaking the curse. The beginnings of the end of the fuku were in Oscar’s rebellion. But if the original curse was put in place by a machismo man whose ultimate power over women caused death and evil, then a woman will be needed to end it once and for all. Who better than someone named after Isis, the goddess who protected the dead and invented marriage? Nice job, Diaz.

Works Cited

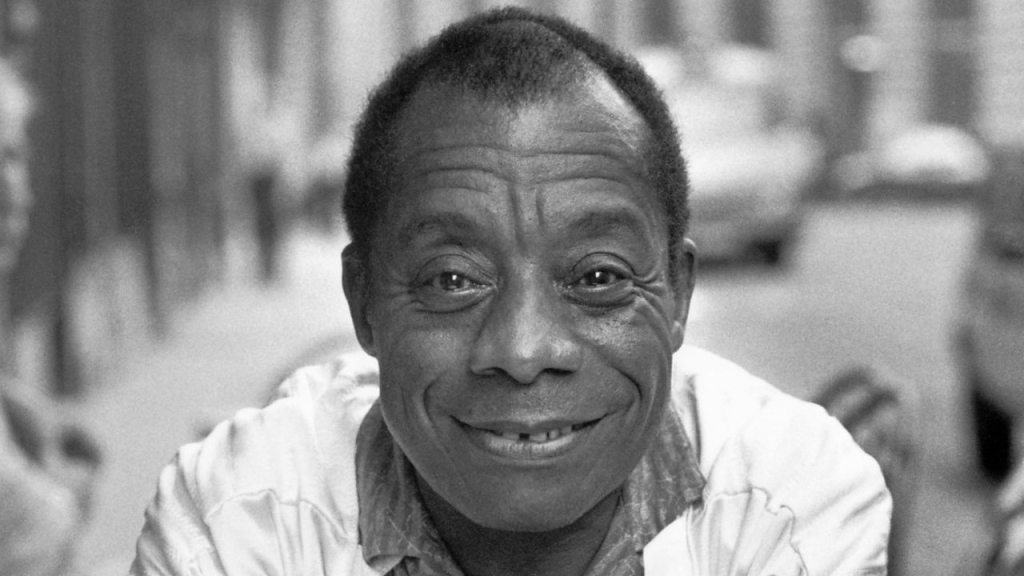

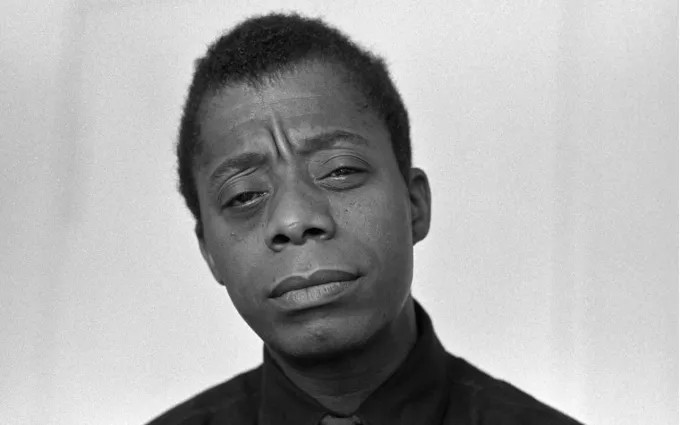

Conrad, Joseph, and D.C.R.A. Goonetilleke. Heart of Darkness. Peterborough, Ont: Broadview, 1999.

Diaz, Junot. The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. Riverhead Books, New York, 2007.

Tyldesley, Joyce. “Isis.” Britannica. Dec. 3, 2020, http://www.britannica.com/topic/Isis-Egyptian-goddess